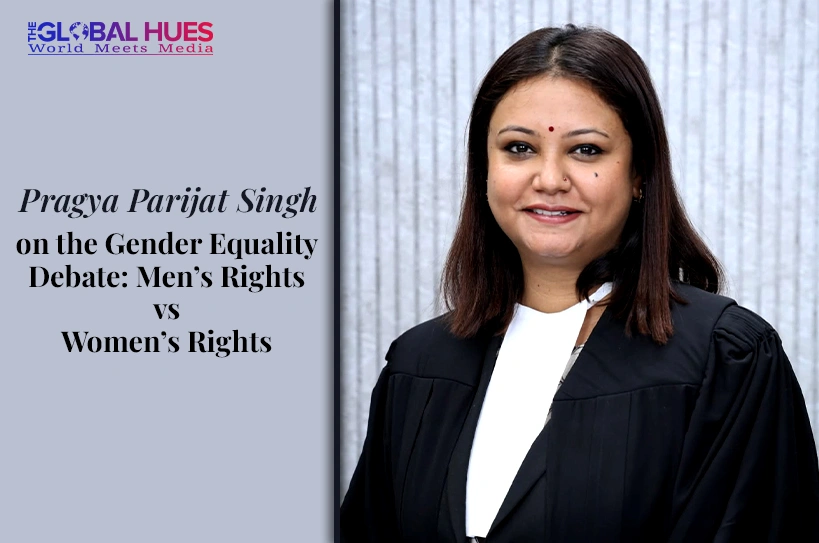

Some careers are planned. Others simply happen. For Advocate-on-Record Pragya Parijat Singh, law was never part of a childhood blueprint. It entered her life quietly, almost by chance and stayed because it felt right.

“I never planned to become a lawyer,” she says honestly. “I was preparing for UPSC. After three attempts, I knew I had to do something. I started going to court because I had no option. But little did I know, I would fall in love with wakalat.”

Born in Prayagraj and based in Delhi, Pragya today is an Advocate-on-Record (AOR) at the Supreme Court of India, one of the few legal professionals authorised to file cases directly before the apex court. But her journey into law was shaped by curiosity and an unexpected sense of purpose.

“There’s a saying, those who do nothing, do wonders,” she laughs. “That’s how law came to me.”

Talking About Men’s Rights Is Not Anti-Women

“Talking about men’s rights doesn’t mean talking against women,” Pragya says firmly. “Human rights belong to everyone. Gender-specific rights were created to correct historical wrongs, but that doesn’t mean imbalance should continue forever.”

She acknowledges that women have been deeply wronged in the past, which led to strong protective laws. But she also believes that time demands reflection.

“If there is a National Commission for Women, why can’t there be one for men?” she asks. “The Constitution talks about equality. Laws should eventually become gender-neutral.”

According to her, misuse of well-intended laws has created a silent crisis.

“When a good law is misused repeatedly, it creates distrust, not just in the system, but in relationships, marriage, and society itself.”

When Protection Turns Into Pressure

Laws like Section 498A, the Domestic Violence Act, and others were designed to protect women from cruelty. But Pragya points out that courts themselves have acknowledged their misuse in multiple judgments.

“Earlier, an FIR under 498A meant immediate arrests,” she explains. “Today, there’s a mandatory mediation process, and that change was necessary.”

She recalls how entire families were once implicated without scrutiny. “There were cases where a sister-in-law living abroad for years was named in an FIR. That’s when the courts realised something had gone wrong.”

Yet, despite amendments, misuse continues, and the impact on men can be devastating. “The moment an FIR is filed, the man is treated as guilty – socially, professionally, emotionally,” she says. “Even if he proves his innocence later, the stigma doesn’t fully go away.”

The Cost of Not Documenting

Pragya shares that many men suffer quietly, often without legal protection or emotional support.

“Mental violence against men is real,” she says. “Threats, emotional blackmail, false accusations, there’s hardly any law that addresses this properly.” While giving advice, she says, “Security is safety. Document everything. Messages, recordings, CCTV, because only proof can protect you.”

She recounts cases where men survived legal battles only because they had evidence, voice recordings, CCTV footage, and documented threats.

“It takes time. There is suffering. But truth backed by proof still holds power in court,” she assures.

Rethinking Justice in Changing Times

Pragya believes the growing mistrust around marriage, especially among younger generations, is a warning sign. “People are scared of marriage today,” she says. “Everything feels transactional. That’s dangerous for society.”

She further adds, “We are making one gender the enemy of another. That’s not justice. Some individuals are problematic, but stereotyping a gender is wrong.”

Pragya strongly advocates for gender-neutral laws while still recognising the need for protection where it’s genuinely required. She says, “Positive discrimination is important. But equality must be the end goal.”

A Voice That Refuses to Stay Silent

Pragya Parijat Singh doesn’t claim to have all the answers, but she asks the right questions. In a legal landscape often dominated by extremes, her voice stands out for its balance, honesty, and courage.

“Justice should protect the vulnerable,” she says. “But it should never destroy the innocent.” And perhaps that is where true reform begins, not in louder laws, but in fairer ones.